This is a proposal for changing the spelling of the French word “crasher” to “cràcher”.

Croissant, Photographed by Jeshoots (CC0)

Introduction

English orthography is a traynrek. For example, the letter combination “ough” is pronounced in all of the following ways:

- /oʊ/1 as in “though” (cf. “toe”)

- /uː/ as in “through” (cf. “true”)

- /ʌf/ as in “rough” (cf. “ruffian”)

- /ɒf/ as in “cough” (cf. “coffin”)

- /ɔː/ as in “thought” (cf. “taut”)

- /aʊ/ as in “bough” (cf. “cow”)

French orthography is a relative delight. In French, there is, in most cases,2 a one-to-one correspondence between, on the one hand, one or more letters and, on the other, a pronunciation. For example, “é”, “et”, “es”, and “ai” are consistently pronounced /e/, a vowel that is similar to one in English “gate”. French orthography is consistent with respect to pronunciation.

French has, for many years, borrowed words from English, changing their spellings to various degrees to reflect French orthography. For instance, French borrowed the English term “riding coat” as “redingote” by AD 1725. The spelling of “redingote” perfectly reflects the French pronunciation /ʁə.dɛ̃.ɡɔt/. French orthography does not use the letter combinations “oa” or “ng”, so the absence of these combinations from the French spelling “redingote” is appropriate.

There is an unfortunate exception to this usual practice of orthographic adaption: “crasher”. Derived from the English verb “to crash”, this French word conveys the same meanings as the English word: for a computer program to experience abnormal termination, to attend a party without invitation, and for a plane to hit the ground at high speed, with disastrous consequences for the plane.

The French pronunciation of “crasher” is /kʁa.ʃe/. The sound represented, using the International Phonetic Alphabet, as ʃ is present in both the English and French words. In English, this sound is often spelt “sh”. In French, it is almost always spelled3 “ch”. But not in “crasher”. The French word uses the alien (to French) spelling “sh” for this sound.

This use is unfortunate. A reader of French who is unfamiliar with both this word and English orthography would have no idea how to pronounce the letter combination “sh”.

Proposed Solution

The easiest solution to the problem described above would be to change the spelling of “crasher” to “cracher”. This spelling, though consistent with French orthography, would create a homonym. “Cracher” already means “to spit”. Homonyms are present in French and are therefore admissible. Consider “vers” (“towards”), “vert” (“green”), “ver” (“worm”), and “verre” (“glass (for drinking)”), all pronounced /vɛʁ/. But the goal of this proposal is to reduce confusion. Overloading “cracher” with another meaning would frustrate this goal.

Fortunately, there is an alternate spelling that is both consistent with French orthography and unambiguously different to “cracher”: “cràcher”. This spelling represents the sound /a/ with “à” rather than “a”. In French orthography, “à”, like “a”, always represents the sound /a/. There is already precedent for using “à” in a disambigutory manner: the word “à”, which means “at”, “to”, “on”, or “from”. The word “a” also exists but means “has”.

This tongue-in-cheek proposal hereby proposes changing the spelling of “crasher” to “cràcher”. This new spelling would be both consistent with French orthography and clearly distinct from the French word for “to spit”.

Another Alternative Considered

The spelling “crâcher”, with a circumflex, would have served the goals described above. Indeed, French already uses the circumflex to prevent homonyms, for example of “sur” (“on”) and “sûr” (“sure”). Most uses in French of the circumflex reflect the loss of the /s/ phoneme, however. Examples are “forêt” (“forest”) and “ancêtre” (“ancestor”). Using a circumflex in this case would result in a different sort of confusion, however. Would the circumflex reflect, a reader might wonder, a lost /s/ phoneme or serve to disambiguate? The proposed solution, using a grave diacritic, avoids this confusion.

Shameless Plug

Though acceptance of my proposal by the Académie Française would fill my heart with joy, my real motive is ulterior. I hope to spur interest in my next iOS app: Conjuguer. This app will allow French learners to browse approximately 6,700 French verbs and study their conjugations. Frequency-of-use data for each verb will help focus the learner’s studies. The app is currently available only as a GitHub repo, but I intend to release a TestFlight beta soon. If this app interests you, please email me at vermontcoder at gmail dot com for an invitation to the beta. Screenshots follow.

| Verb List | Verb |

|---|---|

|

|

| Verb-Model List | Verb Model |

|---|---|

|

|

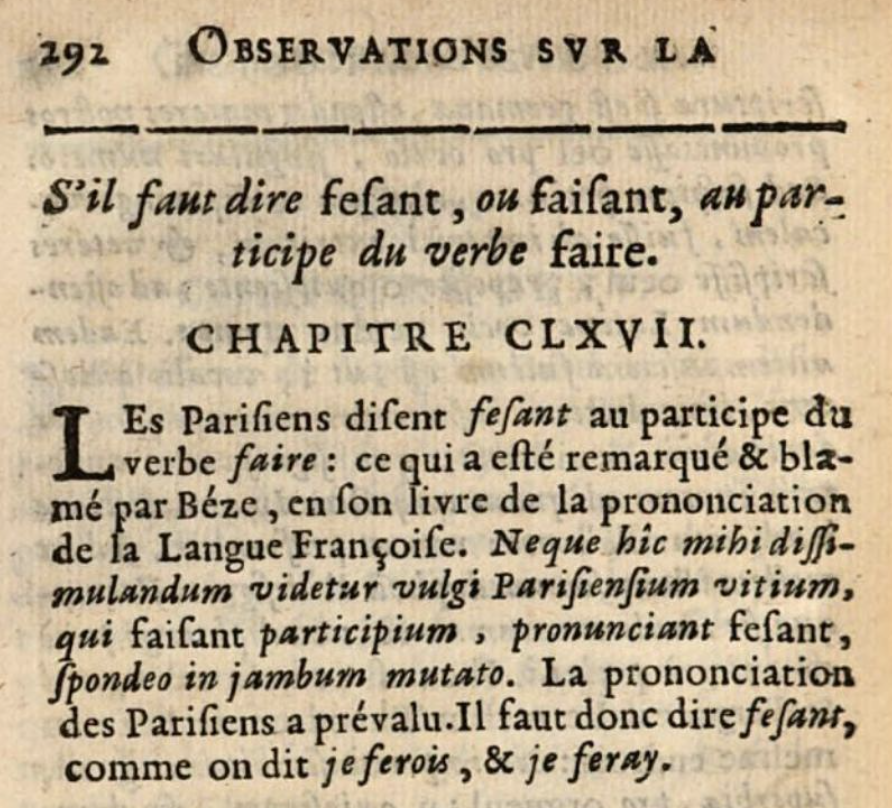

Observations De Monsieur Menage Sur La Langue Françoise, Courtesy of Google Books

-

This post uses, here and elsewhere, the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) in order to represent phonemes. An exegetical disquisition on the IPA is beyond the scope of this post, but I aver that I am an admirer. ↩

-

One exception is the pronunciation of “faisant”: /fə.zɑ̃/, not /fe.zɑ̃/, as spelling suggests. The orthographically consistent spelling of “faisant” would be “fesant”. This lacuna in French’s otherwise admirable orthography reflects an innovation in Parisian pronunciation that prevailed, see above, but that did not affect orthography. ↩

-

Use of the spellings “spelt” and “spelled” represent my cri de cœur, or perhaps de guerre, with respect to English orthography. As an aside, I reject the advice of the Chicago Manual of Style and AP Style Guide to stigmatize so-called foreign words with italics or quotation marks, respectively. “Cheese” is a foreign word just as much as “cri de cœur”. No one italicizes “cheese”, and I don’t see a defensible dividing line. ↩