I recently contributed to SwiftSyntax, a subproject of the Swift open-source project. Building Swift and its subprojects from scratch and then unit-testing them takes about three hours, and the Terminal command is both long and complicated. A build-and-test run can output more than a megabyte to Terminal. Some of this output is potentially useful for diagnosing build-or-test failures. As an iOS developer, I haven’t spent much time in Terminal, but, in the course of running long and long-running Terminal commands recently, I reacquainted myself with some Unix tricks that I developed in the late 90s while working primarily on AIX, which, like macOS, is a Unix. These tricks could potentially benefit anyone running Terminal commands that are long, that take a long time to complete, or that generate a lot of output.

Pondering a Long Terminal Command

Naïve Command

Contributors to Swift and its subprojects invoke a Python script called build-script in order “to build, test, and prepare binary distribution archives of Swift and related tools.” build-script can take many arguments, but the following invocation is typical for building Swift and running its unit tests:

utils/build-script --skip-build-benchmarks --skip-ios --skip-watchos --skip-tvos --swift-darwin-supported-archs "x86_64" --cmake-c-launcher="$(which sccache)" --cmake-cxx-launcher="$(which sccache)" --release-debuginfo --test --infer

Although this command works, I call it a naïve command because it can be greatly improved, as demonstrated below.

Break It Up

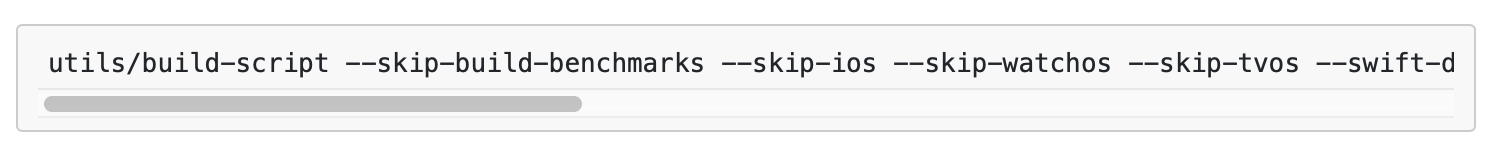

The naïve command is long. So long, for example, that, as I write this blog post and build it using Jekyll, the command is three times wider than what macOS Safari can display without horizontal scrolling.

Safari with Scroll Bar

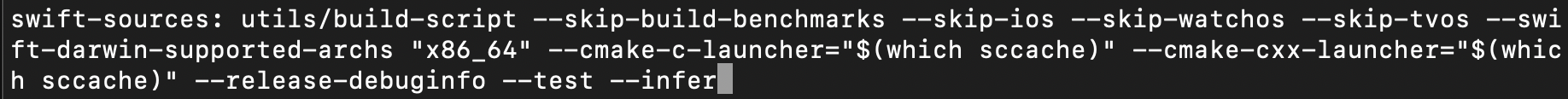

When I paste the command in Terminal, the command wraps in awkward places, right in the middle of swift and which.

Terminal with Long Command

Some of the ten arguments are conceptually related to each other, but the naïve command gives no indication of these relations.

The solution to wrapping and loss of semantic value is to break up the command using \:

utils/build-script \

--skip-build-benchmarks --skip-ios --skip-watchos --skip-tvos --swift-darwin-supported-archs "x86_64" \

--cmake-c-launcher="$(which sccache)" --cmake-cxx-launcher="$(which sccache)" \

--release-debuginfo \

--test \

--infer

This improved command has five conceptual groups of arguments. The last three groups have one argument only and convey the meanings described in build-script’s documentation. But the first two groups convey additional meaning. The first group means, “Skip the stuff not needed for this project: tvOS, watchOS, iOS, ARM, and the Swift Benchmark Suite.” The second group means, “Use sccache to ‘avoid[] compilation when possible, storing cached results … on local disk’.” Grouping arguments on this conceptual basis helps future human readers of the command understand the “skip stuff” and “use sccache” intents that I had when I composed the command.

The broken-up command doesn’t wrap at all in Terminal and almost fits without horizontal scrolling in macOS Safari.

Save the Output

Another problem with the naïve command is that its 1.4 megabytes of output go to Terminal, which discards the output if Terminal becomes RAM-constrained, if I invoke the clear command, or if I quit Terminal. This possible loss of output is unacceptable because the command may fail, in which case I need to examine the output for forensic analysis or to seek the assistance of the Swift cognoscenti. build-script actually launches many sub-processes, and a failure in one of these may not even appear near the end of the output. If Terminal’s scroll buffer isn’t large enough to hold all the output, the failure can disappear into the æther.

The solution is to save the command’s output, stdout and stderr, to a file. Here is how to do that:

utils/build-script \

# omitted for brevity

> ~/Desktop/buildOutput.txt 2>&1

In this invocation, output goes to a file on my desktop. I like to store on my desktop files, including build-script output files, that I intend to eventually delete so that their presence reminds me to delete them.

Play a Sound

Because a build-script invocation takes so long, I don’t stare expectantly at Terminal while it executes. I do something else. A Wikipedia deep dive, for example. Did you know that a natural nuclear reactor spontaneously activated in what is now Gabon 1.7 billion years ago? One did. But I’m eager to continue development when build-script finishes. Rather than periodically glance at Terminal, I listen for my MacBook’s fan. When it stops, build-script is usually finished. But there is a more-reliable way to be informed when a long-running command finishes: have Terminal play a sound after completion of the command. Here is how to do that:

utils/build-script \

# omitted for brevity

; echo $'\a'

Although this approach to playing a sound after completion works for me, the reader should be aware of certain limitations described here.

Time

Knowing how long an invocation like build-script takes is useful. You can brag to friends that a clean build and test takes three hours. More importantly, certain optional arguments may or may not impact running time and, if an optional argument doesn’t affect running time, it’s a good candidate for omission from future invocations. Here is how to use Bash’s built-in time command to time execution:

time utils/build-script \

# omitted for brevity

Here is the output:

real 172m51.465s

user 1267m36.406s

sys 28m0.306s

The first value is real-world elapsed time. Regarding user versus sys time, I lazily quote Wikipedia.

The total CPU time is the combination of the amount of time the CPU or CPUs spent performing some action for a program and the amount of time they spent performing system calls for the kernel on the program’s behalf. When a program loops through an array, it is accumulating user CPU time. Conversely, when a program executes a system call such as

execorfork, it is accumulating system CPU time.

The fact that user + sys time is more than seven times longer than real time implies that build-script runs in a highly concurrent manner. 🙇♂️

Curiously, the time command in this example is built into Bash and is not a free-standing Unix utility. But /usr/bin/time, a BSD utility, exists and produces differently formatted output. Here is the output from /usr/bin/time ls run in the log-file folder for this website. Note the lack of concurrency implied by arithmetic.

7.85 real 5.29 user 1.27 sys

Wrapping Up

Here is the build-script invocation with all of the improvements described above:

time utils/build-script \

--skip-build-benchmarks --skip-ios --skip-watchos --skip-tvos --swift-darwin-supported-archs "x86_64" \

--cmake-c-launcher="$(which sccache)" --cmake-cxx-launcher="$(which sccache)" \

--release-debuginfo \

--test \

--infer \

> ~/Desktop/buildOutput.txt 2>&1 \

; echo $'\a'

I hope you find these four weird Unix tricks useful. Please let me know if you have any suggestions for further improving my build-script invocation.