A significant portion of my workday consists of browsing and grokking code that other people have written. I have had the experience of being frustrated, upon encountering a trailing closure, not knowing the name or therefore purpose of the argument being passed. This frustration initially caused me to consider forswearing trailing closures in my side projects. But with the benefit of contemplation and research, I have concluded that trailing closures are sometimes useful. This post describes how I reached this conclusion, recounts the history of trailing closures, and describes an analog from Kotlin.

"This file needs a trailing closure."

Definitions and Example

Apple defines closures as “self-contained blocks of functionality that can be passed around and used in your code” and describes trailing closures as follows:

If you need to pass a closure expression to a function as the function’s final argument and the closure expression is long, it can be useful to write it as a trailing closure instead. A trailing closure is written after the function call’s parentheses, even though it is still an argument to the function. When you use the trailing closure syntax, you don’t write the argument label for the closure as part of the function call.

Here is an example of code not using a trailing closure:

@IBOutlet weak var label: UILabel!

@IBAction func fade() {

let fadeDuration: TimeInterval = 1.0

UIView.animate(withDuration: fadeDuration, animations: {

self.label.alpha = 0.0

})

}

fade() uses UIView.animate() to reduce the alpha of a UILabel named label to 0.0, causing the label to disappear. The animations: argument is a closure.

Here is the same code using a trailing closure:

@IBOutlet weak var label: UILabel!

@IBAction func fade() {

let fadeDuration: TimeInterval = 1.0

UIView.animate(withDuration: fadeDuration) {

self.label.alpha = 0.0

}

}

Note the absence of any label for the animations: argument. The parameter list ends after the withDuration: argument, and the closure begins.

The Problem

If you are a seasoned Apple-ecosystem developer, you probably would have found the second snippet easy to grok even if it had not been preceded by the first. This is likely because UIView.animate() is an API of great antiquity and is in widespread use. But imagine encountering, for the first time, the following use of a trailing closure:

performSetup {

fatalError("Setup failed.")

}

The purpose of performSetup() is clear from the name, but the purpose of the trailing closure is not. Without looking at the function definition, the reader might guess that the trailing closure runs if any error occurs during setup. This guess would be incorrect, as the definition demonstrates:

func performSetup(onUnrecoverableError: () -> Void) {

var unrecoverableErrorHappened = false

// Perform setup, setting unrecoverableErrorHappened

// to true if an unrecoverable error happened.

if unrecoverableErrorHappened {

onUnrecoverableError()

}

}

The closure runs not if any error happens but rather if an unrecoverable error happens. This would have been clear, without looking at the definition, if the performSetup() call had not used a trailing closure:

performSetup(onUnrecoverableError: {

fatalError("Setup failed.")

})

The name of the argument, onUnrecoverableError:, would have made clear the purpose of the closure. As Microsoft observed, “Named arguments … improve the readability of your code by identifying what each argument represents.” The first invocation of performSetup() above is less readable than the second because the absence of a named argument obscures what the closure represents, that is, the intended use of the closure. This obscuring was the source of my frustration described in the introduction to this blog post. As noted above, this frustration initially caused me to consider forswearing trailing closures in my side projects.

One might counter my argument that trailing closures obscure purpose by observing that nothing prevents the code reader from jumping to the definition of the function being called, thereby seeing the argument’s name and (hopefully) divining the argument’s purpose. This observation is correct. But I’m not arguing that trailing closures make it impossible to discern an argument’s name and therefore purpose. Rather, I argue that having to jump to the definition can slow the process of understanding an API usage. When a significant portion of one’s day consists of grokking code, these repeated jumps to definitions add up to a tangible loss of productivity.

Findings

Heterodox eschewal of trailing closures would be, I realized, grist for a blog post. By way of research for that blog post, I surveyed the Swift cognoscenti as to the history of, and use case for, trailing closures by posting the following inquiry on the Swift Forums:

I am researching a blog post in which I will argue that trailing closures sometimes are not conducive to maximum code clarity and maintainability. To that end, I would like to ask this forum a couple questions about trailing closures. First, what language, if any, inspired their inclusion in Swift? I heard Ruby, but I don’t have confirmation of that. Second, why do folks use them? Some reasons I can think of are terseness, not having to include the argument label or closing paren, and desire to follow the prevailing practice.

Several commenters stated that they do not avoid trailing closures but rather restrict their use.

Erica Sadun suggested, “Perhaps you should consider whether the closure is being used procedurally or functionally in your writeup. I follow [Lily Ballard]’s lead, trying to restrict them to procedural applications.”

AEC observed that “I use them when I want to convey I’m doing something like what a classical loop does with a braces wrapped block of code.”

jawbroken wrote the following:

I think you’re missing the obvious reason to use it, and probably the main motivating factor for implementing trailing closure syntax in a language: it allows you to make custom constructs that look like native control flow. This allows libraries to extend the language in a natural way, e.g. in the Dispatch module, without having special support in the compiler. In this sense they serve a similar purpose to operator overriding and custom operator definitions.

These replies clarified the use cases for trailing closures and reassured me of the precedent for using them in some, but not all, situations. Upon reflection, I am convinced that trailing closures do not harm clarity of uses of well-known APIs, for example UIView.animate() and DispatchQueue.main.asyncAfter(). I’ve already shown UIView.animate(). Here is DispatchQueue.main.asyncAfter with a trailing closure:

let fadeDelay: TimeInterval = 1.0

DispatchQueue.main.asyncAfter(deadline: .now() + fadeDelay) {

self.label.alpha = 0.0

}

Here is use of that API without a trailing closure:

let fadeDelay: TimeInterval = 1.0

DispatchQueue.main.asyncAfter(deadline: .now() + fadeDelay, execute: {

self.label.alpha = 0.0

})

The purpose of the function, to do some work later, is clear from the name of the function, so the purpose of the closure, to do some work, is clear without the argument label.

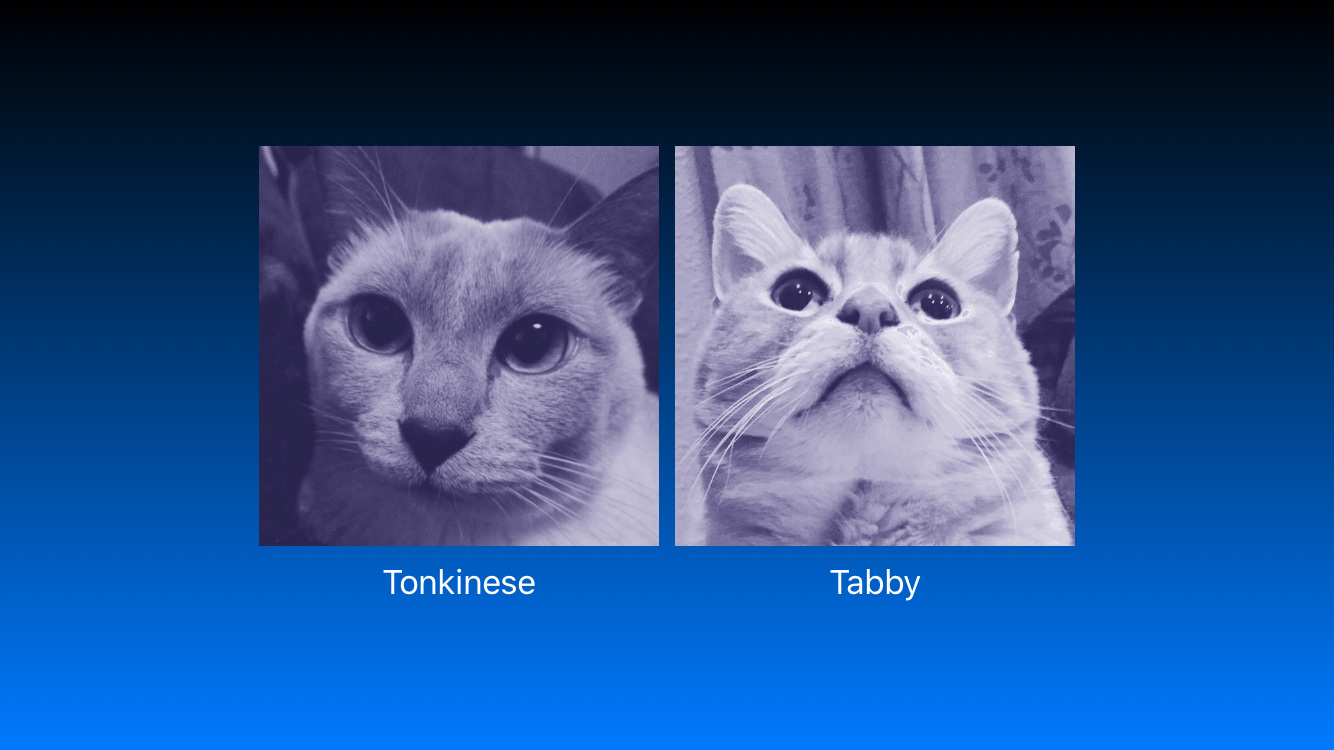

The next example is from SwiftUI. I’ve included a screenshot so the reader can more easily visualize what the code does.

Cats from Stacks

Here is the code with idiomatic uses of trailing closures on ZStack, HStack, and VStack:

var body: some View {

ZStack {

LinearGradient(gradient: Gradient(colors: [.black, .blue]), startPoint: .top, endPoint: .bottom)

HStack {

VStack {

Image(uiImage: UIImage(named: tonkName) ?? fallbackImage)

.resizable()

.frame(width: imageSize, height: imageSize, alignment: .center)

Text(tonkLabel)

.foregroundColor(.white)

}

VStack {

Image(uiImage: UIImage(named: tabbyName) ?? fallbackImage)

.resizable()

.frame(width: imageSize, height: imageSize, alignment: .center)

Text(tabbyLabel)

.foregroundColor(.white)

}

}

}

}

Here is the code with non-idiomatic non-uses of trailing closures:

var body: some View {

ZStack(content: {

LinearGradient(gradient: Gradient(colors: [.black, .blue]), startPoint: .top, endPoint: .bottom)

HStack(content: {

VStack(content: {

Image(uiImage: UIImage(named: tonkName) ?? fallbackImage)

.resizable()

.frame(width: imageSize, height: imageSize, alignment: .center)

Text(tonkLabel)

.foregroundColor(.white)

})

VStack(content: {

Image(uiImage: UIImage(named: tabbyName) ?? fallbackImage)

.resizable()

.frame(width: imageSize, height: imageSize, alignment: .center)

Text(tabbyLabel)

.foregroundColor(.white)

})

})

})

}

The named arguments content: are visual noise because the purpose of the closures is obvious: to describe the content of the ZStack, HStack, or VStack. Swift has a strong tradition of enabling reduction of visual noise, as evidenced by the fact that end-of-line semi-colons are not only optional in the language but discouraged by at least one style guide. This tradition does have limits, however, as evidenced by certain objections to a Swift Evolution proposal for eliding commas from multiline expression lists.

History of Trailing Closures

Chris Lattner, primary creator of the Swift language, described the history of and reasons for trailing closures as follows:

[The trailing closure] is largely a result of my early work on Swift, but there was never any pushback along the years as other folks joined on.

For my part, the original driving reason was to be able to implement “control flow like” structures in the standard library. If you go all the way back, you’ll see that I was originally trying to implement if and other statements in the standard library, and this led to some wacky stuff (e.g. overloading juxtaposition) that was eventually abandoned.

Besides that, I was aware of Ruby, but the bigger issue was the Objective-C design pattern that encouraged blocks to be the last argument, and the goal to make that feel more natural and nicer.

That said, the actual closure syntax iterated a bunch, the first recorded entry in the changelog talks about it. We went through pipe syntax and other experiments as well.

As far as I can tell, the pull request for trailing closures, which must have been raised on or about July 10, 2013, the date in the changelog, is not publicly accessible because the first pull request in the public repo was closed on November 9, 2015. If a reader points me to the trailing-closure pull request, I will gratefully include a citation and discussion of that pull request in this blog post.

Analogous Construct from Kotlin

Kotlin has the equivalent of a closure, a lambda, a function that is, as described by the Kotlin documentation, “not declared, but passed immediately as an expression.” Kotlin lacks named parameters, except as an IDE feature that can be toggled off, so there is no direct equivalent of Swift’s trailing closure in Kotlin. But Kotlin does permit a lambda argument to be placed after the argument list for a function. The existence of this precedent outside the Swift language strengthens my comfort with trailing closures.

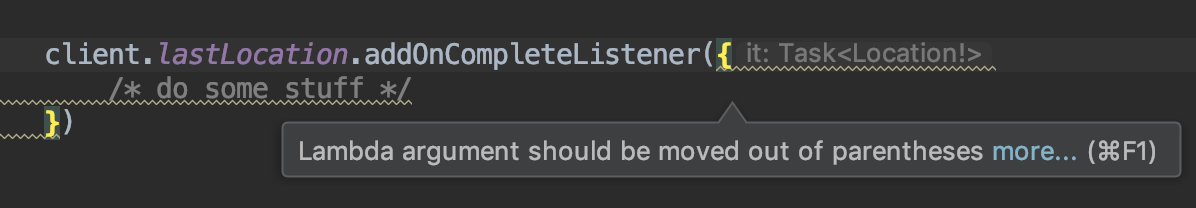

Here is Android Studio’s default suggestion of this outside-parentheses placement:

Android Studio Recommending Outside-Parentheses Placement of Lambda

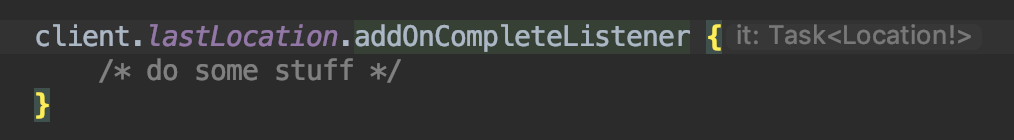

Here is the same code after application of the fixit:

Lambda Placement After Application of Fixit

This fixit likely reflects the Kotlin style guide, which instructs, “If a call takes a single lambda, it should be passed outside of parentheses whenever possible.”